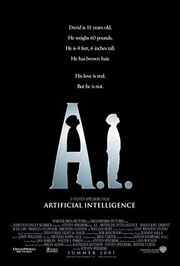

A.I. Artificial Intelligence

| A.I. Artificial Intelligence | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Directed by | Steven Spielberg |

| Produced by | Steven Spielberg Stanley Kubrick Jan Harlan Kathleen Kennedy Walter F. Parkes Bonnie Curtis |

| Written by | Short story Brian Aldiss Screen story: Ian Watson Screenplay: Steven Spielberg |

| Narrated by | Ben Kingsley |

| Starring | Haley Joel Osment Frances O'Connor Jude Law Sam Robards Jake Thomas William Hurt |

| Music by | John Williams |

| Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński |

| Editing by | Michael Kahn |

| Studio | Amblin Entertainment |

| Distributed by | DreamWorks Warner Bros. |

| Release date(s) | June 29, 2001 |

| Running time | 146 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $100 million |

| Gross revenue | $235,926,552 |

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, also known as Artificial Intelligence: A.I. or simply A.I., is a 2001 Academy Award nominated science fiction film directed, co-produced and co-written by Steven Spielberg. Based on Brian Aldiss' short story "Super-Toys Last All Summer Long", the film stars Haley Joel Osment, Frances O'Connor, Jude Law, Sam Robards, Jake Thomas and William Hurt. Set sometime in the future, A.I. tells the story of David, a child-like android programmed with the unique ability to love.

Development of A.I. originally began with Stanley Kubrick in the early 1970s. Kubrick hired a series of writers up until the mid-1990s, including Brian Aldiss, Bob Shaw, Ian Watson and Sara Maitland. The film languished in development hell for years because Kubrick felt computer-generated imagery was not advanced enough to create the David character, whom he believed no child actor would believably portray. In 1995 Kubrick handed A.I. to Steven Spielberg, but the film did not gain momentum until Kubrick's death in 1999. Spielberg remained close to Watson's film treatment for the screenplay, and replicated Kubrick's secretive style of filmmaking. A.I. was greeted with mostly positive reviews from critics and became a moderate financial success. This film was dedicated to Kubrick's memory with a small credit after the credits, saying "For Stanley Kubrick"

Contents |

Plot

Global warming has led to ecological disasters all over the world, along with occluding humanity itself. Humanity's best efforts to maintain civilization have led to the creation of new robots known as "mechas"; advanced humanoid robots which are capable of emulating thoughts and emotions. David (Haley Joel Osment), is an advanced prototype model created by Cybertronics, a manufacturer of mechas, which is designed to resemble a human child and to virtually feel love for its human owners. Cybertronics test this newest creation on one of their employees, Henry Swinton (Sam Robards), and his wife Monica, (Frances O'Connor). The Swintons have a son named Martin (Jake Thomas), who has been placed in suspended animation until a cure can be found for his rare disease. Although Monica is initially frightened of David, she eventually warms to him after activating his imprinting protocol, which irreversibly causes David to feel love for her as a child loves a mother. As David continues to live with the Swintons, he is befriended by Teddy (voiced by Jack Angel); a wise, robotic teddy bear (Supertoy) who takes upon himself the responsibility of David's well-being.

Martin is suddenly cured and brought home; a sibling rivalry ensues between Martin and David. Martin's cruel and scheming behavior backfires when he and his friends activate David's self-protection programming at a pool party; David gets frightened and clings to Martin, inadvertently pulling him into the pool. Alarmed, Henry decides to destroy David at the factory where he was built, but Monica instead leaves him (alongside Teddy) in a forest to live as unregistered mechas. David is captured for an anti-mecha Flesh Fair, an event where obsolete or damaged mechas are destroyed before cheering crowds. David almost ends up getting destroyed by a barrel of acid, but the crowd is swayed by David's pleas for mercy, and he escapes along with Gigolo Joe (Jude Law), a male prostitute mecha who is on the run after being framed for murder by the husband (Enrico Colantoni) of one of his clients.

The two set out to find the Blue Fairy, whom David remembers from the story The Adventures of Pinocchio. As in the story, he believes that she will transform him into a real boy, so Monica will love him and take him back. Joe and David make their way to the decadent metropolis of Rouge City. Information from a holographic volumetric display answer engine called "Dr. Know" (voiced by Robin Williams) eventually leads them to the top of the Rockefeller Center in the flooded ruins of New York City, using a submersible vehicle they have stolen from the authorities, still hot on Joe's tail. When they arrive at New York, David's creator Professor Hobby (William Hurt) enters, after David destroys an android that looks exactly like him, and excitedly tells David that finding him was a test, which has demonstrated the reality of his love and desire, something no other robot could do until now. In Professor Hobby's office, David finds a room full of Davids and Darlenes (David's female counter-parts), packaged and ready to sell to anyone looking for "A love of their own." A disheartened David attempts to commit suicide by falling from a ledge into the ocean, but Joe rescues him. A little while later, Joe is captured by the authorities, but David escapes.

David and Teddy take the submersible to the fairy, which turns out to be a statue from a submerged attraction at Coney Island. Teddy and David are trapped when the Wonder Wheel falls on their vehicle. Believing the Blue Fairy to be real, he asks to be turned into a real boy, repeating his wish without end, until the ocean freezes.

The film switches to the 5th millennium. Humanity has become extinct and New York is buried under several hundred feet of glacial ice.[1] Earth is now being excavated and studied by the descendants of the mechas, now silicon-based supermechas possessing some form of telekinesis and telepathy.[2] They find David and Teddy, the only two functional mechas who knew living humans. David wakes up, finds the frozen stiff Blue Fairy, and tries to touch her. However, because of the time passed and the damage to the statue, it cracks and collapses immediately. David realizes that the fairy was fake. Using David's memories, the supermechas reconstruct the Swinton home, and explain to him via a mecha of the Blue Fairy (voiced by Meryl Streep) that he cannot become human. However, they create a clone of Monica from a lock of her hair which has been faithfully saved by Teddy, and restore her memories from the space-time continuum. However, one of the supermechas (voiced by Ben Kingsley) explains that she will live for only one day and that the process cannot be repeated. David spends the happiest day of his life playing with Monica and Teddy. The ephemeral Monica tells David that she loves him as she drifts slowly away from the world. This was the "everlasting moment" David had been looking for; he closes his eyes, and goes "to that place where dreams are born".

Cast

- Haley Joel Osment as David: An android, known as a mecha, created by Cybertronics programmed with the ability to love. He is adopted by Henry and Monica Swinton, but a sibling rivalry ensues once their son Martin comes out of suspended animation. Osment was Spielberg's first and only choice for the role. The two had met before Spielberg finished the screenplay. Osment decided it was best not to blink his eyes to perfectly portray a robot. He also set himself to have good posture.[3]

- Frances O'Connor as Monica Swinton: David's adopted mother who reads him The Adventures of Pinocchio. She is first displeased to have David at her house but soon falls in love with him. Monica is devastated when it is decided to abandon David.

- Jude Law as Gigolo Joe: A male prostitute mecha programmed with the ability to love, like David, but in a different sense. Gigolo Joe uses songs such as "I Only Have Eyes for You" and "Bobbie, Walter" to seduce women. He meets David at a Flesh Fair and takes him to Rouge City. Law took inspirations from Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly for the portrayal of Gigolo Joe.[4]

- Sam Robards as Henry Swinton: An employee at Cybertronics and husband of Monica. Henry is reluctant to have David home and soon feels David is becoming a danger to the family.

- Jake Thomas as Martin Swinton: Henry and Monica's first son who was placed in suspended animation. When Martin comes back, he convinces David to cut off a lock of Monica's hair.

- William Hurt as Professor Allen Hobby: He is responsible for commissioning the creation of David. He resides in the ruined city Manhattan. It is revealed that David is modeled after Hobby's own son named David, who seems to have died at a young age.

Jack Angel provides the voice of Teddy, while Brendan Gleeson cameos as Lord Johnson-Johnson, the owner and master of ceremonies of the Flesh Fair. Robin Williams voices Dr. Know, Meryl Streep voices Blue Fairy, Ben Kingsley narrates the film as the leader of the futuristic mechas, and appears briefly as one of the technicians who repairs David after he eats spinach; Chris Rock plays/voices a mecha killed at the Flesh Fair, and Adrian Grenier plays a teen in van.

Soundtrack

Production

Stanley Kubrick began development on an adaptation of "Super-Toys Last All Summer Long" (which he eventually retitled A.I.) in the early 1970s, hiring the short story's author, Brian Aldiss to write a film treatment. In 1985 Kubrick brought longtime friend Steven Spielberg to produce the film,[5] along with Jan Harlan. Warner Bros. agreed to co-finance the film and cover distribution duties.[6] A.I. labored in development hell, with Aldiss being fired over creative differences in the late 1980s.[7] Bob Shaw served as writer very briefly, leaving after six weeks because of Kubrick's demanding work schedule. Kubrick then hired Ian Watson to write the film in March 1990. Aldiss later remarked, "Not only did the bastard fire me, he hired my enemy [Watson] instead." Kubrick handed Watson The Adventures of Pinocchio for inspiration, calling A.I. "a picaresque robot version of Pinocchio".[6][8]

Three weeks later Watson gave Kubrick his first story treatment, and concluded his work on A.I. in May 1991 with another treatment, at 90-pages. Gigolo Joe was originally conceived as a GI character, but Watson suggested changing him to a gigolo. Kubrick joked "I guess we lost the kiddie market."[6] In the meantime, Kubrick dropped A.I. to work on a film adaptation of Wartime Lies, feeling computer animation was not advanced enough to create the David character. However, after the release of Jurassic Park (with its innovative use of computer-generated imagery), it was announced in November 1993 that production would begin in 1994.[9] Dennis Muren and Ned Gorman, who worked on Jurassic Park, became visual effects supervisors,[7] but Kubrick was displeased with their previsualization, and the expense of hiring Industrial Light & Magic.[2]

Stanley [Kubrick] showed Steven [Spielberg] 650 drawings which he had, and the script and the story, everything. Stanley said, "Look, why don't you direct it and I'll produce it." Steven was almost in shock.

In early 1994 the film was in pre-production with Christopher "Fangorn" Baker as concept artist, and Sara Maitland assisted on the story, which gave it "a feminist fairy-tale focus".[6] Maitland said that Kubrick never referred to the film as A.I., but as Pinocchio.[2] Chris Cunningham became the new visual effects supervisor. Some of his unproduced work for A.I. can be seen on the DVD The Work of Director Chris Cunningham.[11] Aside from considering computer animation, Kubrick also had Joseph Mazzello do a screen test for the lead role.[2]

Cunningham helped assemble a series of "little robot-type humans" for the David character. Harlan said "We tried to construct a little boy with a movable rubber face to see whether we could make it look appealing. But it was a total failure, it looked awful." Hans Moravec served as a technical consultant.[2] Meanwhile, Kubrick and Harlan thought A.I. would be closer to Steven Spielberg's sensibilities as director.[12][13] Kubrick handed the director's position to Spielberg in 1995, but Spielberg chose to direct other projects, and convinced Kubrick to remain as director.[10][14] Kubrick then put the film on hold due to his commitment to Eyes Wide Shut (1999).[15] After the filmmaker's death in May 1999, Harlan and Christiane Kubrick approached Spielberg to take over the director's position.[16][17] By November 1999 Spielberg was writing the screenplay based on Watson's 90-page story treatment. It was his first solo screenplay credit since Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977).[18] Spielberg remained close to Watson's treatment, but removed various sex scenes with Gigolo Joe, which Kubrick had in mind.[13]

Pre-production was briefly halted during February 2000, because Spielberg pondered directing four other projects, which were Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, Minority Report, Memoirs of a Geisha, and a Charles Lindbergh biopic.[15][19] When he decided to fast track, Spielberg brought Chris Baker back as concept artist.[14] The original start date was July 10, 2000[13] but filming was delayed until August.[20] The Swinton house was constructed on Stage 16 at Warner Bros. Studios, while Stage 20 was used for other sets. A.I. was mostly shot on sound stages, except for a couple of scenes in Oregon.[21][22] Spielberg copied Kubrick's obsessively secretive approach to filmmaking by refusing to give the complete script to cast and crew, banning press from the set, and making actors sign confidentiality agreements. Scientist Cynthia Breazeal served as technical consultant during production.[13][23] Haley Joel Osment and Jude Law applied prosthetic makeup daily in an attempt to look "shinier, very robotic-like".[3] Bob Ringwood (Batman, Troy) served as the costume designer. For the citizens of Rouge City, Ringwood studied people on the Las Vegas Strip.[24] Spielberg also found post production on A.I. difficult because he was simultaneously preparing to shoot Minority Report.[25]

Warner Bros. used an alternate reality game titled The Beast to promote the film. Over forty websites were created. There were to be a series of video games for the Xbox video game console that followed the storyline of The Beast, but they went undeveloped. To avoid audiences mistaking A.I. for a family film, no action figures were created, although Hasbro released a talking Teddy following the film's release in October 2001.[13] A.I. had its premiere at the Venice Film Festival in 2001.[26] The film opened in 3,242 theaters in the United States on June 29, 2001, earning $29,352,630 during its opening weekend. A.I went on to gross $78.62 million in US totals as well as $157.31 million in foreign countries, coming to a worldwide total of $235.93 million.[27] A.I. earned twice as much money overseas than it did in North America, which is a rare occurrence. The film was a modest financial success since it recouped more than twice the amount of its $100 million budget.

Reception

The film received generally positive reviews. Based on 181 reviews collected by Rotten Tomatoes, 73% of the critics gave the film positive notices. The website described the critical consensus perceiving the film as "a curious, not always seamless, amalgamation of Kubrick's chilly bleakness and Spielberg's warm-hearted optimism. [The film] is, in a word, fascinating."[28] By comparison Metacritic collected an average score of 65, based on 32 reviews.[29]

Producer Jan Harlan stated that Kubrick "would have applauded" the final film, while Kubrick's widow Christiane also enjoyed A.I.[30] However, Brian Aldiss was vocally displeased with the film stating, "It’s crap. Science fiction has to be logical, and it’s full of lapses in logic."[31] Richard Corliss heavily praised Spielberg's direction, as well as the cast and visual effects.[32] Roger Ebert wrote that it was "Audacious, technically masterful, challenging, sometimes moving [and] ceaselessly watchable. [But] the movie's conclusion is too facile and sentimental, given what has gone before. It has mastered the artificial, but not the intelligence."[33] Jonathan Rosenbaum compared A.I. to Solaris (1972), and praised both "Kubrick for proposing that Spielberg direct the project and Spielberg for doing his utmost to respect Kubrick's intentions while making it a profoundly personal work."[34] Film critic Armond White, of the New York Press, praised the film noting that "each part of David’s journey through carnal and sexual universes into the final eschatological devastation becomes as profoundly philosophical and contemplative as anything by cinema’s most thoughtful, speculative artists–Borzage, Ozu, Demy, Tarkovsky."[35]

James Berardinelli found the film "consistently involving, with moments of near-brilliance, but far from a masterpiece. In fact, as the long-awaited 'collaboration' of Kubrick and Spielberg, it ranks as something of a disappointment." He particularly criticized the ending: ‘The film's final half-hour is a curiosity, and not a successful one — a prolonged, needless epilogue which force-feeds us a catharsis that feels as false as it is extraneous to an otherwise fine story.’[36] Mick LaSalle gave a largely negative review. "A.I. exhibits all its creators' bad traits and none of the good. So we end up with the structureless, meandering, slow-motion endlessness of Kubrick combined with the fuzzy, cuddly mindlessness of Spielberg." Dubbing it Spielberg's "first boring movie", LaSalle also believed the robots at the end of the film were aliens, and compared Gigolo Joe to the "useless" Jar Jar Binks, yet praised Robin Williams for his portrayal of a futuristic Albert Einstein.[37] Peter Travers gave a mixed review, concluding "Spielberg cannot live up to Kubrick's darker side of the future."[38] Spielberg responded to some of the criticisms of the film, stating that many of the "so called sentimental" elements of A.I., including the ending, were in fact Kubrick's and vice-versa the darker elements were his own.[39] However, Sara Maitland, who worked on the project with Kubrick in the 1990s, claimed that one of the reasons Kubrick never started production on AI was because he had a hard time making the ending work.[40]

"People pretend to think they know Stanley Kubrick, and think they know me, when most of them don't know either of us," Spielberg told film critic Joe Leydon in 2002. "And what's really funny about that is, all the parts of A.I. that people assume were Stanley's were mine. And all the parts of A.I. that people accuse me of sweetening and softening and sentimentalizing were all Stanley's. The teddy bear was Stanley's. The whole last 20 minutes of the movie was completely Stanley's. The whole first 35, 40 minutes of the film – all the stuff in the house – was word for word, from Stanley's screenplay. This was Stanley's vision."

"Eighty percent of the critics got it all mixed up. But I could see why. Because, obviously, I've done a lot of movies where people have cried and have been sentimental. And I've been accused of sentimentalizing hard-core material. But in fact it was Stanley who did the sweetest parts of A.I., not me. I'm the guy who did the dark center of the movie, with the Flesh Fair and everything else. That's why he wanted me to make the movie in the first place. He said, 'This is much closer to your sensibilities than my own.'"[41]

Visual effects supervisors Dennis Muren, Stan Winston, Michael Lantieri and Scott Farrar were nominated the Academy Award for Visual Effects, while John Williams was nominated for Original Music Score.[42] Steven Spielberg, Jude Law and Williams received nominations at the 59th Golden Globe Awards.[43] The visual effects department was once again nominated at the 55th British Academy Film Awards.[44] A.I. was successful at the Saturn Awards. Spielberg (for his screenplay), the visual effects department, Williams and Haley Joel Osment (Performance by a Younger Actor) won in their respective categories. The film also won Best Science Fiction Film and for its DVD release. Frances O'Connor and Spielberg (as director) were also nominated.[45]

In late 2009, film critic A.O. Scott named A.I. the second best film of the 2000s, calling it "the most misunderstood movie of the past ten years" and Spielberg's "unsung masterpiece".[46]

The film appeared on several 'Best of the 2000s' film lists. In the Film Comment poll, it was ranked as 30th.[47] Slant magazine ranked it 23rd.[48] Finally, Indie Wire rated it 10th in their Best of the Decade Critics Survey 2000s.[49]

References

- ↑ Jim Windolf (2007-12-02). "Q&A: Steven Spielberg". Vanity Fair. http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/features/2008/02/spielberg_qanda200802?currentPage=4. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "The Kubrick FAQ Part 2: A.I.". The Kubrick Site. http://www.visual-memory.co.uk/faq/index2.html#slot14. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Haley Joel Osment, A Portrait of David, 2001, Warner Home Video; DreamWorks

- ↑ Jude Law, A Portrait of Gigolo Joe, 2001, Warner Home Video; DreamWorks

- ↑ Scott Brake (2001-05-10). "Spielberg Talks About the Genesis of A.I.". IGN. http://movies.ign.com/articles/200/200038p1.html. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "Plumbing Stanley Kubrick". Ian Watson. http://www.ianwatson.info/kubrick.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Steven Gaydos (2000-03-15). "The Kubrick Connection". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117779484. Retrieved 2008-07-19.

- ↑ Dana Haris (2000-03-15). "Spielberg lines up A.I., Report". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117779498. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ↑ Christian Moerk (1993-11-02). "A.I. next for Kubrick at Warners". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR115550. Retrieved 2008-07-07.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kenneth Plume (2001-06-28). "Interview with Producer Jan Harlan". IGN. http://movies.ign.com/articles/300/300920p1.html. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ "The Work of Director Chris Cunningham". NotComing.com. http://www.notcoming.com/features/cunningham/. Retrieved 2008-07-19.

- ↑ "A.I. Artificial Intelligence". Variety. 2001-05-15. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117799373. Retrieved 2008-07-19.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Liane Bonin (2001-06-28). "Boy Wonder". Entertainment Weekly. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,165660,00.html. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Steven Spielberg, Jan Harlan, Kathleen Kennedy, Bonnie Curtis, Creating A.I., 2001, Warner Home Video; DreamWorks

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Christian Moerk (1999-12-23). "Spielberg encounters close choices to direct". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117760260. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ↑ Scott Brake (2001-06-29). "Producing A.I.". IGN. http://movies.ign.com/articles/300/300984p1.html. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ↑ Army Archerd (1999-07-15). "Annie Tv'er nab tops talent". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117742990. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ Michael Fleming (1999-11-16). "West pursues Prisoner; Spielberg scribbles". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117758075. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ↑ Peter Bart (2000-01-24). "It's scary up there". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117761198. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ↑ Brian Zoromski (2000-06-30). "A.I. Moves Full Speed Ahead". IGN. http://movies.ign.com/articles/034/034162p1.html. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ↑ Scott Brake (2000-08-03). "A.I. Set Reports!". IGN. http://movies.ign.com/articles/034/034165p1.html. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ↑ Christopher "Fangorn" Baker, Rick Carter, A.I. From Drawings to Sets, 2001, Warner Home Video; DreamWorks

- ↑ Bill Higgins (2000-11-06). "BAFTA hails Spielberg". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117788785. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ↑ Bob Ringwood, Dressing A.I., 2001, Warner Home Video; DreamWorks

- ↑ Charles Lyons (2001-01-18). "Inside Move: Cruise staying busy". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117792198. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ↑ David Rooney (2001-04-16). "'Dust' in the wind for Venice fest". Variety. http://www.variety.com/index.asp?layout=festivals&jump=story&id=1061&articleid=VR1117797100&cs=1. Retrieved 2008-07-19.

- ↑ "A.I. Artificial Intelligence". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=ai.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ↑ "A.I. Artificial Intelligence". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/ai_artificial_intelligence/. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ↑ "A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001): Reviews". Metacritic. http://www.metacritic.com/video/titles/ai?q=A.I.. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- ↑ Army Archerd (2000-06-20). "A.I. A Spielberg/Kubrick prod'n". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117801772. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ↑ Bryan Appleyard (2007-12-012). "Why don't we love science fiction?". Times Online. http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/books/article2961480.ece. Retrieved 2009-09-05.

- ↑ Richard Corliss (2001-06-17). "A.I. – Spielberg's Strange Love". Time. http://www.time.com/time/sampler/article/0,8599,130942,00.html. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ↑ "A.I. Artificial Intelligence". Roger Ebert. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20010629/REVIEWS/106290301/1023. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ↑ Jonathan Rosenbaum (2001-06-29). "The Best of Both Worlds". Chicago Reader. http://www.chicagoreader.com/movies/archives/2001/0107/010713.html. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ↑ White, Armond (2001-07-04). "Spielberg's A.I. Dares Viewers to Remember and Accept the Part of Themselves that Is Capable of Feeling". The New York Press. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ James Berardinelli (2001-06-29). "A.I.". ReelViews. http://www.reelviews.net/movies/a/ai.html. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ↑ Mick LaSalle (2001-06-29). "Artificial foolishness". San Francisco Chronicle. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2001/06/29/DD239232.DTL. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ↑ Peter Travers (2001-06-21). "A.I. Artificial Intelligence". Rolling Stone. http://www.rollingstone.com/reviews/movie/5949345/review/5949346/ai_artificial_intelligence. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ↑ "Steven Spielberg". Mark Kermode. The Culture Show. 2006-11-04.

- ↑ http://www.visual-memory.co.uk/faq/index2.html#slot14 The Kubrick FAQ Part 2.

- ↑ Joe Leydon (2002-06-20). "'Minority Report' looks at the day after tomorrow -- and is relevant to today". Moving Picture Show. http://www.movingpictureshow.com/dialogues/mpsSpielbergCruise.html. Retrieved 2009-04-29.

- ↑ "Academy Awards: 2002". Internet Movie Database. http://www.imdb.com/Sections/Awards/Academy_Awards_USA/2002. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ "59th Golden Globe Awards". Internet Movie Database. http://www.imdb.com/Sections/Awards/Golden_Globes_USA/2002. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ "55th British Academy Film Awards". Internet Movie Database. http://www.imdb.com/Sections/Awards/BAFTA_Awards/2002. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ "Saturn Awards: 2002". Internet Movie Database. http://www.imdb.com/Sections/Awards/Academy_of_Science_Fiction_Fantasy_And_Horror_Films_USA/200. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ Disney (date unknown). Retrieved from http://bventertainment.go.com/tv/buenavista/atm/specials/bestofthedecade/index.html.

- ↑ http://www.filmlinc.com/b/?p=1490

- ↑ http://www.slantmagazine.com/film/feature/best-of-the-aughts-film/216/page_8

- ↑ http://www.indiewire.com/survey/best_of_the_decade_critics_survey_2000s/best_of_the_decade

External links

- Official website

- A.I. Artificial Intelligence at the Internet Movie Database

- A.I. Artificial Intelligence at Allmovie

- A.I. Artificial Intelligence at Rotten Tomatoes

- A.I. Artificial Intelligence at Box Office Mojo

- Super-Toys Last All Summer Long

- Jude Law Interview by Charlie Rose

- Spielberg's AI: Another Cuddly No-Brainer by Stevan Harnad

- Jon Bastian (2001-07-13). "A.I. in Depth". Filmmonthly.com. http://www.filmmonthly.com/Behind/Articles/AIinDepth/AIinDepth.html.

- AI by Timothy Kreider originally printed in Film Quarterly.

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by X-Men |

Saturn Award for Best Science Fiction Film 2001 |

Succeeded by Minority Report |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||